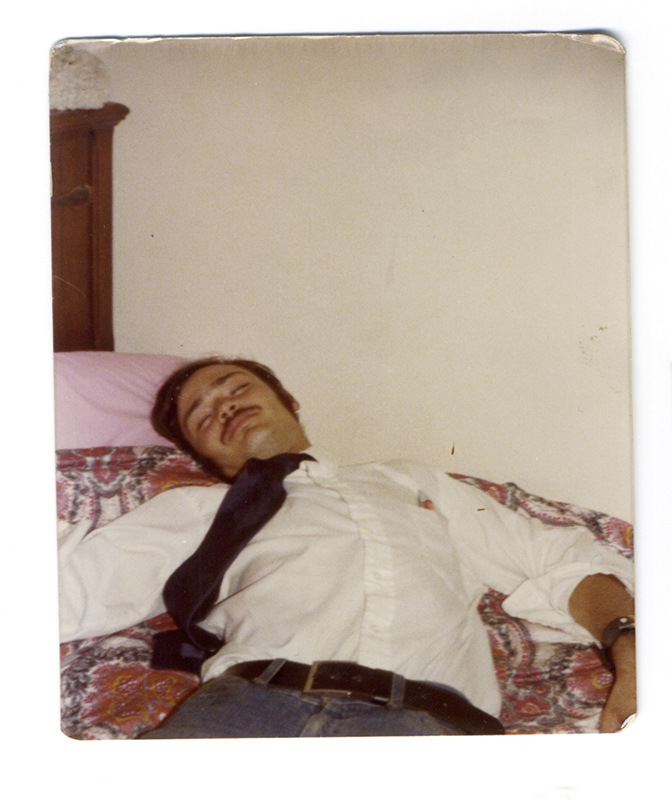

Patrick Pound - People who look dead but (probably) aren't

Patrick Pound evokes both the seriousness and silliness of life. He obsessively collects old photographs, and assembles them in idiosyncratic clusters, where odd and unexpectedly common subjects emerge. He re-creates the world, forging relationships between images and presenting them as one - as if “meaning might be found in the accumulation of details, as if the world’s just some vast series of overlapping lists and if we can find the last piece we’ll solve the puzzle”. This exhibition presents three of Pound’s collections, each finding fun in our collective oddities, while revealing sweeping, awkward truths about real lives and real feelings.

One of Pound’s categories gives the exhibition its name, People who look dead but (probably) aren’t. It’s a hopeful title that describes a collection of fallen, frail, tired looking souls, who in coming together, give each other a new and unexpected life. It’s Pound’s use of ‘probably’ that makes this work so funny and so perplexing. Where a car crash leaves a man slumped behind the wheel, and a woman is face down on a tennis court,we're also faced with an uncomfortable incomprehension: can we laugh or should we not?

In his other works too, Pound reveals that the magic of found photos is in their genuine ambiguity. While we might normally look first to faces for clues of context and character, People from behind, gives us little more to go by than pairs of slacks and cuts of suit. And although it might seem at first like a good excuse to carefully consider other peoples’ backsides, the work also brings our own proclivity forstorytelling and snap judgments to the fore.

Where heads are scratched through with precision, facial features neatly penned-out, and whole bodies whited out of existence in Damaged, we’re left to guess why its subjects were quite literally defaced. Perhaps it is telling, in a creepy and sad sort of way, that despite the injuries and scrawled insults, these photos are otherwise intact. Like indexical records of cold angers and hardened hurts, they make pain genuinely palpable, not indicating what might have happened so much as how what happened might have felt. The dark irony here is that it possibly wasn’t the photos, but their owners, who sustained the worst damage.

By highlighting the ‘probablys’ and ‘possiblys’ in our relationship with these images, Pound reminds us that meanings are fragile, and interpretations slippery. However, by avoiding saying something solid, his work says so much more. These throwaway snaps en masse describe our relationships more honestly than the perfectly posed ones amassing on our mantles. Especially the complicated and emotional relationship we have with the camera.